In the past decades, the number of people living with overweight, obesity, and diet related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has risen. This increase has been associated with widening exposure to obesogenic food environments in Europe and globally.

The food environment is defined as a combination of physical, economic, political, and sociocultural surroundings as well as opportunities and conditions that influence food choice. It incorporates geographic access, food availability, food affordability and food quality. Over past decades, food environments have become increasingly unhealthy, for example ultra-processed foods are now widely available. Previous research from the European Union, revealed that there is potential for the EU to improve its policies influencing food environments.

The aim of this study was to evaluate food policy implementation in European countries and identify priority actions for governments to create healthy food environments. The Food-EPI tool and process guided the analysis in each country (Slovenia and Portugal aligned the process with the evaluation of national Food and Nutrition action plans).

The Food EPI- tool includes seven policy domains representing characteristics of food environments:

- food composition,

- food labelling,

- food promotion,

- food prices,

- food provision,

- food retail, and

- food trade and investment.

With six infrastructure domains:

- leadership,

- governance,

- funding and resources,

- monitoring and intelligence,

- platforms for interaction and

- health policies in all.

The tool was adapted to the context of each country using a six-step process. This included a collection of evidence on the implementation of food policies summarised into a document verified by national government officials. Based on this evidence document, the level of implementation of food environment policies was assessed considering the extent of the policy implementation and coverage at national level compared to international best practice.

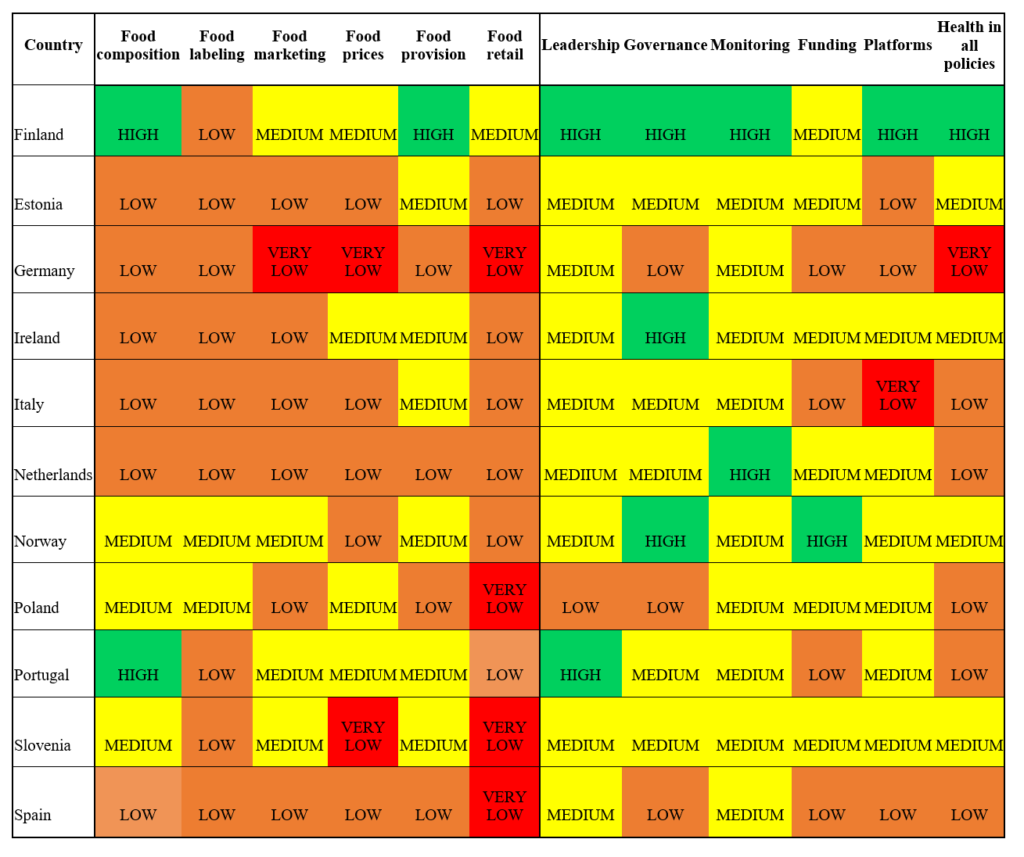

Findings revealed that Finland had the highest proportion (32% n=7/22) of policies influencing food environments with a high level of implementation. Whereas Slovenia and Poland had the highest proportion of policies rated at low implementation (42% n=10/24 and 36% n =9/25 respectively). Retail was rated the lowest policy domain and the lowest rated infrastructure domain was ‘health in all policies’ (table 1). The only policy domains whereby a country was rated as ‘high’ was food composition (Portugal and Finland) and Food Provision (Finland). Finland had high implementation across the board for infrastructure domains, except for funding (table 1).

Table 1: Level of policy infrastructure support and implementation in European countries

(Pineda et al. 2022)

Overall, the implementation of preventative policies remains low with slow progress, but small improvement has been observed for recent years. The improvement of school environments was high on European countries priorities as well as the need to regulate marketing to children. These were key priorities for consulted experts, along with fruit and vegetable subsides and unhealthy food and beverage taxation.

There is much potential for European countries to improve their food policies and infrastructure support influencing food environments. The key next steps are to distribute the recommendations of the study to policy makers and the uptake of recommendations by public health organisations. A systems approach is essential to support enabling of healthier food environments to tackle obesity and NCDs in European countries.

Read the full publication here